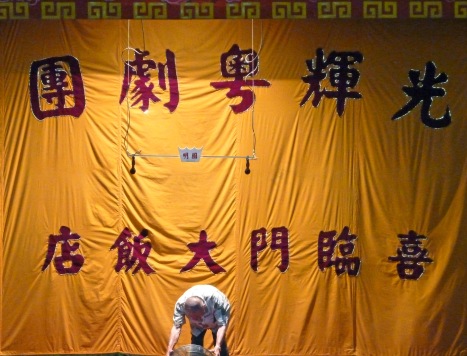

Last night, on a lawn – nay, a grass patch – in Singapore’s Chinatown along Kreta Ayer Road, a wooden stage was erected on stilts under a sprawling canvas tent. Almost all the plastic chairs were filled by gleeful, chuckling elderly aunties and uncles, two tourists, and one younger woman with a large camera, alternating between that and Instagramming the Chinese opera performance everyone was enthralling in. The cloying soprano arias and melodies of wayang (a local Malay term for live plays) drifted from speakers on stage left and right, sucked from a solo microphone hanging from the rafters, as incense smoke wisped its way from the makeshift Taoist altars on the other end of the tent; all these molecules met in the middle over the heads and produced a metaphysical reaction best described as star-kissed moonshine, that state of being in the right moment, the sweet spot, the sensation of knowing there was nowhere else to be.

About one hundred meters away in Kreta Ayer Square was another tent, this one of nylon, a projected image of Scottish chef Will Meyrick on one end. The soundtrack was not the cacophony of Chinese instruments and gong strikes, but ambient electronica percussioned by the frequent maracas of cocktails and ice being shaken. Old men peered in, and wondered why their usual chess spots had morphed into a luminescent bar counter. Not even Usain Bolt could have covered this distance and not wonder if he’d false started into a different dimension. But it’s not as extreme as you’d think.

Chatting with Chinatown boss James Ong, he reiterated that the area has always ushered progress without closing one eye on the rear-view mirror of celebrating traditions. It’s this peripheral vision that’s driven the heritage district to what it is today, with some of Singapore’s best restaurants, bars and creative juice harmonizing with generations-old shophouses, businesses built by immigrants, and local street food where it all started. But for the next two weeks, we’ll forget the cheesy contrivances of Club Street, be comforted even though stalwart hawker ground zero Maxwell Road Food Center is closed, because Gastrogig will be unfurling the cuisines of Meyrick and chef Peeter Piehl of Estonia in their now-legendary pop-up presentations.

Setting up a mobile kitchen on a Chinatown street, then laying out tables and chairs to enjoy some of the best food that can be found in Southeast Asia? That’s as Singaporean eating as you can get, and that’s the current rendition of Gastrogig over the upcoming fortnight. Thirty years ago, my grandfather held my hand as we wove through crowded Smith Street to share a table with strangers at pre-air-conditioning Tak Po, dim sum splayed in front of us. This weekend, I’ll shake hands with people I’ll meet for the first time, pull seats up to our mutual table, and chow in union. Last night’s canapés gave a taste of what the Chef Meyrick mettle was all about:

A version of Indonesian corn fritters, a light encasement instead of a heavier batter. © Desiree Koh

Ask Chef Meyrick how he got from the Scottish isles to Balinese archipelago (with a stop in that continent masquerading as island, Australia), and he’ll say, “By plane.” The truth lies in the tome that is Inspirations of Sarong, the cookbook Meyrick spent two years working on to capture everything native Asians – particularly of the Southeast variety – already know: our street food kicks your food trucks’ asses. (I love a great taco al pastor, empanada, Chicago-style hot dog, kofta, kebab, &c. as much as another eater with 10 stomachs but come on, what’s taken the world so long to realize braised pig’s intestines and banh mi will put you on the rocketship to galactic gastronomy?) Oh, the stories he’ll tell – the 45-year-old Phnom Penh woman who had never been on a plane before, whom he flew back to Bali so she could teach him how to cook Cambodian. The 60-year-old Beijing dumpling mistress who only spoke in Chinese proverbs, that also returned with him to Denpasar to impart her skills. She now wants to travel every year.

Tuna betel – stuff all and all into your mouth, addictive not just because of the leaf. © Desiree Koh

“That’s what food is about for me,” says Meyrick. “It’s communication, an old language that depicts religion, history, culture. As long as you’re cooking the food of a culture, you’ve got to know the history of the people first, and then you can start to understand how they live.”

Washington oysters in red namh jihm, beautiful bivalves coming out of their shells only to be plunged into flaming Thai spice. © Desiree Koh

The chef recalls going into the homes of strangers to tune his craft, and will soon be traversing “the four corners of Thailand cooking with old ladies” for his next project.

“I hope you guys will also get the inspiration to believe in street food and where food comes from. With Asian food, we’re not re-creating anything – what we’re trying to do is keep it alive.”

After I left the Gastrogig tent, I went over to the wayang tent to watch the rest of the Cantonese opera, wishing my grandmother (signature dishes: braised pig’s trotters in sweet vinegar, Hakka taro abacus beads, lotus root and pork soup) was with me.